Crowded housing... the greatest challenge for Yolŋu families

Click here for access to the "Invisible Homeless" journal article reporting these findings in more detail.

Insufficient, insecure and/or inadequate housing are serious and enduring problems for remote Aboriginal families in the Northern Territory (NT) and social, health, educational and economic consequences are extensive.

Public housing is the only option in many remote Aboriginal communities as there is no private rental or house ownership.

Most young families rely on extended family to provide accommodation. At best, parents and all their children share one room or an already crowded space in a living area. Sometimes the only option is a tent in the yard. Some move from house to house and never find a secure and stable space in which to bring up their children. In effect they are homeless.

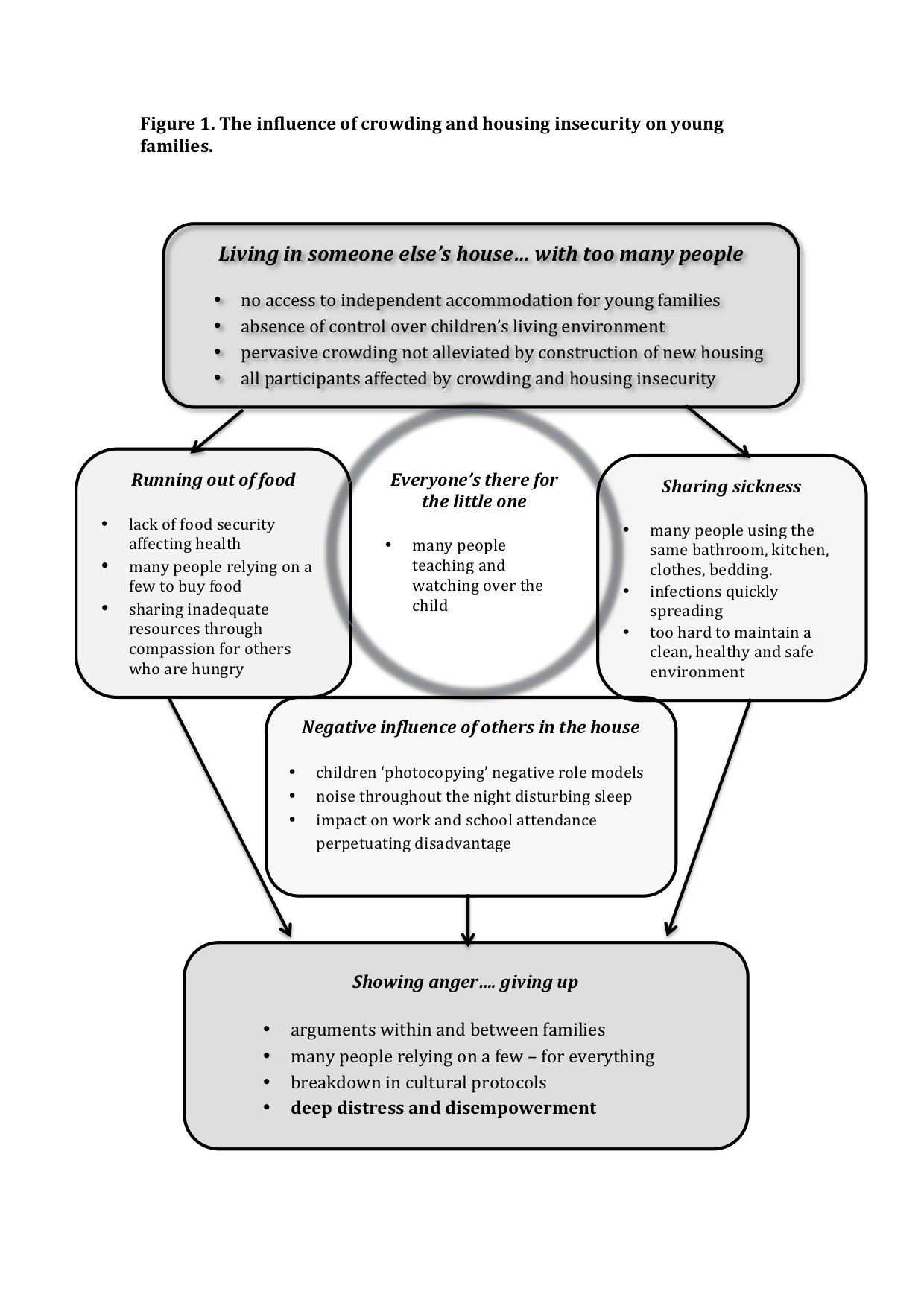

... ‘Living in someone else’s house with too many people’ – reflects the interlinked concepts of crowding and housing insecurity and illuminates the absence of control over the conditions in which families are bringing up their children. These two elements – housing insecurity and insufficiency - underpin many challenges associated with housing1.

Yolŋu families described the consequences of this homelessness for their children and how it impacts on the families’ capacity to look after children in the ways they know are important but find difficult if not impossible to achieve. Below are just a few examples of their experiences and many more are described in the journal article reporting these findings in more detail.

Food security is a serious challenge and days without food are common:

In the midst of their own hardship these families feel compassion for others so they help other people in the house when they are hungry – and then their own food is gone. We buy food and everyone relies on one Yolŋu and then the food is all gone… sometimes, no food - 3 days, 4 days. We saved food for Gamarraŋ and mother and father had no food, only water. If we have our own house we will have plenty of food in the house. We are finding it too hard (Gamarraŋ’s mother)1

In the midst of their own hardship these families feel compassion for others so they help other people in the house when they are hungry – and then their own food is gone.

Now I’ve got no money for food, I’ve got no food in the house… ‘cause everybody keeps coming and getting from us. And it’s really hard, I try hard to hide things from people but it’s wrong to do that… I just give it away… Because I feel that person’s really sick and hungry. But another time, I get sick and hungry.1

Sleep disturbance due to noise throughout the night impacts on work and school attendance and living in crowded conditions generates conflict within and between families.

Often others in the house don’t take responsibility for paying rent, buying food, cleaning or paying for power – relying on a few in the household to do it all.

(Families) also worry about sickness spreading due to many people in a small space, sharing one bathroom and kitchen.

In most houses, while many people share the same toilet and shower, only a few take responsibility for cleaning. Bedding, plates, cutlery and cooking utensils are in short supply when many people borrow items and don’t return them so everyone has to share the few things available:

…a lot of people get flu and it spreads to the kids… sharing drinks, sharing food, sharing one spoon… a lot people using one toilet and one shower... (Gamarraŋ’s parents).

The negative influence of other, often older children – swearing, teasing, playing day and night – and no opportunity for young families to spend time together and with their children in their own space are also concerns.

All participants shared their distress about living in crowded houses where parents have so little control over the environment in which they are bringing up their children. However, some explained that there are also benefits from living with many family members:

Get together for the little one. So there’s everyone there for the little one, nurturing, sharing responsibilities. And teaching the little one (Baŋadi’s grandfather).1

In a crowded house children can learn from family members of different ages, providing greater support for children’s learning than can be provided by parents alone. Opportunities for children to acquire cultural knowledge that families consider important are enhanced when many people are continuously interacting with the child:

…Raypirri (strong education about the right way to behave) and also gurruṯu (kinship) and rom (law). Family education… (Gudjuk’s mother).

This learning is reinforced until the knowledge is internalised by the child:

It’s like everyone will talk to the child, his mother, his father, his aunty, his uncle, grandmother, grandfather and everyone tells him the same thing… Talking with strong voice to your child, day and night, and your child will listen, keep repeating the strong words and they will hear it over and over and finally it is their idea. (Yolŋu researcher’s observation).

Many family members living in the house also means that there are more people watching over children to protect them and keep them safe. The support and connection with other family members is central in the lives of all participants but the distress from the negative aspects of living in crowded conditions – sometimes with people who are not close family – was often overwhelming....

The challenges of crowded and insecure housing – not enough sleep, not enough food or energy for school or work, the negative influence of others in the house, sharing sickness, conflict and stress – were shared by all participants. Many were frustrated that the reality they live with every day is not recognised beyond the community and they are blamed for problems that they have no power to prevent. All were striving to provide a supportive environment in which to bring up their children, but disempowerment and defeat were often the result of these constant challenges:

… they just give up. They’ve had enough. They lose their courage (Baŋadi’s grandmother).1

Crowding and housing insecurity must be addressed if Aboriginal children are to have the opportunity to develop their full potential.

1. Lowell A, Maypilama EL, Fasoli L, Gundjarranbuy R, Godwin-Thompson J, Guyula A, Yunupiŋu M, Armstrong E, Garrutju J, McEldowney R. The ‘invisible homeless’: challenges faced by families bringing up their children in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:1382